‘Hipster’ has become the ultimate sensibility in popular culture in the first decade of the 2000’s. Searching for a real definition of what a ‘hipster’ is, I soon hit the borders of the Internet. It seems that no subculture before had so many haters as the hipster culture. Why is it that even documentaries by the serious German television channels Arte and ZDF criticize it as a ‘dead end culture’?

Simon Reynolds is a well-known music journalist. Some years ago he published the book Retromania. Pop-Culture’s Addiction to its Own Past, dealing with the retro/nostalgia/vintage syndrome of our time. Douglas Haddow, also journalist, wrote the influential article Hipster: The Dead End of Western Civilization. Let us hear what the experts have to say about the hipster-phenomenon.

Phobia against a counter-culture by outsiders is nothing new. The new thing with critics on hipster culture is its intensity:

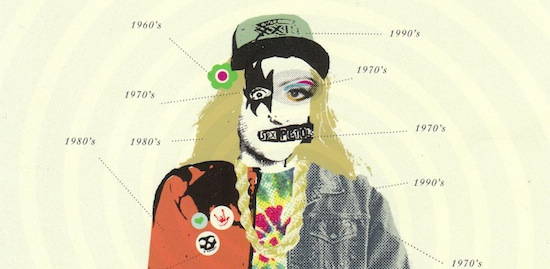

Visually a hipster is to be easily identified by stereotypical fashion and accessories, like “skinny jeans, cotton spandex leggings, fixed-gear bikes, vintage flannel, fake eyeglasses and a keffiyeh” [2], but also different tools and gadgets by Apple Macintosh, like iPhones, iPads and iPods are oft-seen additions to make a hipster’s outfit complete. The latter are status symbols rather than just phones or computers. This also reveals the social provenance of hipsterdom: “You can find this curator/creative class – the quasi-bohemia known pejoratively as hipsters – in any city in the developed world that is large and affluent enough to support a decent-sized upper middle class”. [3: 169].

Visually a hipster is to be easily identified by stereotypical fashion and accessories, like “skinny jeans, cotton spandex leggings, fixed-gear bikes, vintage flannel, fake eyeglasses and a keffiyeh” [2], but also different tools and gadgets by Apple Macintosh, like iPhones, iPads and iPods are oft-seen additions to make a hipster’s outfit complete. The latter are status symbols rather than just phones or computers. This also reveals the social provenance of hipsterdom: “You can find this curator/creative class – the quasi-bohemia known pejoratively as hipsters – in any city in the developed world that is large and affluent enough to support a decent-sized upper middle class”. [3: 169].

Haddow also points out that, while other counter-cultures like punks and hip-hoppers wore and wear their couture with pride as a method of self-expression and rebellion, that “it is rare, if not impossible, to find an individual who will proclaim themself a proud hipster. It’s an odd dance of self-identity – adamantly denying your existence while wearing clearly defined symbols that proclaims it” [2]. Music writer Simon Reynolds had a similar observation: “In many people’s minds, retro is twinned with hipster, another identity that almost nobody embraces voluntarily, even when they outwardly appear to fit the profile completely” [3: xxxii].

The rejection by hipsters to be named as such may have several different reasons. Through all the hipster-phobia the refusal of a label keeps them from criticism from outsiders. It would be always possible to say “I am not one of those”.

Hipsters – who engross the concept of ‘authenticity’ – tend to label those ‘hipsters’, who, in their opinion, are inauthentic. Therefore, the term has a negative meaning among the hipster-culture.

The denial of the label may be also a form of “subcultural bad consciousness”, because some of the criticism on the values the hipster-culture embraces appears to be justified.

One argument is the “retro” facet, the fact that the hipster culture worships the past so much. Hipsters are “the same cutting-edge class” [3: xiv] as the bohemians (that is, the avant-garde) used to be, “but instead of being pioneers and innovators, they’ve switched roles to become curators and archivists” [3: xivi]. Reynolds comes to the conclusion that “postmodern hipsterati don’t have any culturally generative power” [3: 170].

One argument is the “retro” facet, the fact that the hipster culture worships the past so much. Hipsters are “the same cutting-edge class” [3: xiv] as the bohemians (that is, the avant-garde) used to be, “but instead of being pioneers and innovators, they’ve switched roles to become curators and archivists” [3: xivi]. Reynolds comes to the conclusion that “postmodern hipsterati don’t have any culturally generative power” [3: 170].

Another critic is that the hipster culture “borrows” symbols of identification from other subcultures, but abandon their meanings, e.g. the keffiyeh, which “initially sported by Jewish students and Western protesters to express solidarity with Palestinians […] has become a completely meaningless hipster cliché fashion accessory” [2].

Haddow further criticizes the hipster culture, for representing a counter-culture that “[w]e’ve reached a point in our civilization where counterculture has mutated into a self-obsessed aesthetic vacuum. So while hipsterdom is the end product of all prior countercultures, it’s been stripped of its subversion and originality” [2].

Maybe the strongest stricture comes from hipsters’ attitude towards consumerism:

Hipsterdom is the first “counterculture” to be born under the advertising industry’s microscope, leaving it open to constant manipulation but also forcing its participants to continually shift their interests and affiliations. Less a subculture, the hipster is a consumer group – using their capital to purchase empty authenticity and rebellion. [2]

Haddow even goes so far to claim that the hipster “represents the end of Western civilization – a culture lost in the superficiality of its past and unable to create any new meaning” or “a culture so detached and disconnected that it has stopped giving birth to anything new” [2]. Previous youth movements, “[p]roviding the soundtrack for rebellion, […] felt compelled to slay their fathers rather than pay tribute to them” [3]. “[T]oday we have the ‘hipster’ – a youth subculture that mirrors the doomed shallowness of mainstream society” [2].

Haddow even goes so far to claim that the hipster “represents the end of Western civilization – a culture lost in the superficiality of its past and unable to create any new meaning” or “a culture so detached and disconnected that it has stopped giving birth to anything new” [2]. Previous youth movements, “[p]roviding the soundtrack for rebellion, […] felt compelled to slay their fathers rather than pay tribute to them” [3]. “[T]oday we have the ‘hipster’ – a youth subculture that mirrors the doomed shallowness of mainstream society” [2].

The criticism of the two journalists seems harsh, but they have a point there. However, there is still a constructive way onward for the hipster culture if they finally found a way to be creative on their own, to once again become the avant-gardists, since “the avant-garde is now an arriere-garde” [3: xx]. Perhaps then they could wear their label with pride and even make things that their descendants would in the future deem worthy of their retro-appreciation.

Sources

[1] Carr, N.

2011 ‘Past-Tense Pop’ (2011-08-04), <http://www.tnr.com/book/review/retromania-simon-reynolds>, retrieved: January 25st 2013.

[2] Haddow, D.

2008 ‘Hipster: The Dead End of Western Civilization’. Adbusters (2008-07-29). Retrieved: January 21st 2013.

[3] Reynolds, S.

2011 Retromania. Pop-Culture’s Addiction to Its Own Past. New York: Faber & Faber.